21 Year Tax Holiday for Foreign Cloud: A Red Carpet for Big Tech, a Red Signal for Local Heroes?

Synopsis: India’s 2047 tax holiday for foreign cloud firms may draw up to USD 200 billion in data-centre investment and accelerate AI infrastructure, yet it tilts the market toward Big Tech. Limited jobs, power use, US CLOUD Act exposure, and tax disadvantages for domestic players could threaten energy security, sovereignty, and innovation. India has offered […] The post 21 Year Tax Holiday for Foreign Cloud: A Red Carpet for Big Tech, a Red Signal for Local Heroes? appeared first on Trade Brains.

Synopsis: India’s 2047 tax holiday for foreign cloud firms may draw up to USD 200 billion in data-centre investment and accelerate AI infrastructure, yet it tilts the market toward Big Tech. Limited jobs, power use, US CLOUD Act exposure, and tax disadvantages for domestic players could threaten energy security, sovereignty, and innovation.

India has offered a long tax holiday to foreign cloud companies to speed up the building of data centres and strengthen its digital infrastructure. While the move could bring big investments and new technology, it has also raised concerns about power demand, limited jobs, and the future of local tech players. Is this a bold step toward digital leadership, or a policy that may cost India more than it gains?

21 Year Tax Break

The government has offered a long-term tax break to attract global cloud and data centre companies to India. In the Union Budget 2026-27, the Finance Ministry proposed a tax holiday running all the way until 2047 for foreign firms that set up and operate data centres in the country, provided they meet certain conditions.

While presenting the Budget on February 1, Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman said that India needs strong digital infrastructure and large investments in data centres. To encourage this, she announced that any foreign company providing cloud services to customers worldwide using Indian data centres would be eligible for this tax exemption till 2047.

However, the benefit does not come without rules. One key condition is that foreign cloud providers must serve Indian customers through a local Indian reseller company rather than selling services directly. If the data centre operator in India is a related company within the same multinational group, it can charge a profit margin of up to 15 percent over cost under what is known as “safe harbour” rules.

These safe harbour rules, defined under Section 92CB of the Income-tax Act, mean that tax authorities will accept the pricing between related companies as fair, as long as it stays within the approved margin. In simple terms, this reduces disputes over pricing between multinational companies and the tax department.

Why?

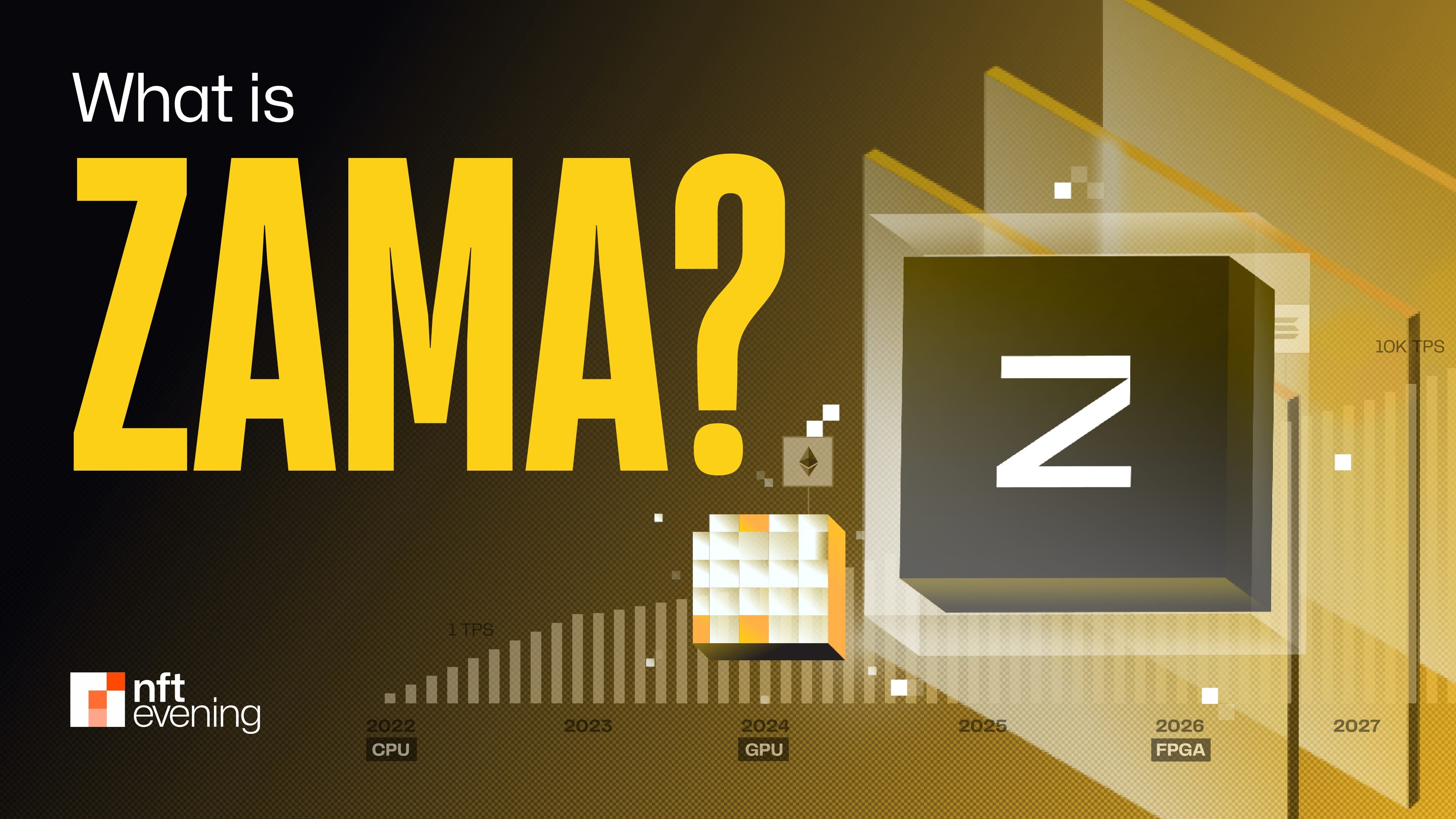

The push for data centres is closely linked to the rise of artificial intelligence. Building large AI systems does not just require smart algorithms and huge amounts of data, it also needs massive computing power. This computing power comes from data centres (large facilities spread across acres of land that house millions of servers running advanced chips). These centres consume enormous amounts of electricity and water, making them critical but resource-heavy infrastructure for the digital economy.

According to real estate firm Colliers, India had around 1,263 megawatts of data-centre capacity across seven major cities as of April 2025. This capacity is expected to grow rapidly and could cross 4,500 megawatts by 2030, bringing in USD 20-25 billion in fresh infrastructure investment.

Global tech giants are already moving in this direction. Google, Microsoft and Amazon Web Services (AWS) have announced multi-billion-dollar plans in India. Google, in partnership with the Adani Group, is planning a USD 15-billion data-centre campus in Visakhapatnam focused on AI workloads.

At the same time, AWS has committed USD 12.7 billion by 2030, while Microsoft has signalled similar expansion plans. These investments show a race among global cloud players, and the new tax holiday is designed to speed this up. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) also reported that foreign direct investment into India jumped by 73 percent in 2025, partly driven by growing cloud and data-centre activity. In other words, global money is already flowing toward India’s digital infrastructure, and the tax incentive may turn interest into real, on-ground projects.

However, while investors are excited, some industry experts remain cautious about the long-term impact. Many global players now see AI infrastructure as a major export opportunity for India, similar to how software services once became a key strength of the country.

After the Budget announcement, IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said that total investments in India’s data-centre sector could rise to USD 200 billion, compared to the USD 70 billion currently in progress. He also noted that several AI server manufacturers are showing interest in setting up operations in India, indicating a broader ecosystem developing around cloud and AI hardware.

Why the Red Carpet Could Become a Red Signal for India?

While the 2047 tax holiday may attract massive investment, several structural risks could turn this “red carpet” for Big Tech into a warning sign for India’s economy, energy security, and digital future.

Low Job-to-Power Ratio

Data centres consume huge amounts of electricity but create relatively few direct jobs. A typical 12-megawatt data centre generally needs only about 20 to 22 operational staff to function properly. These include technicians, engineers, and system administrators who monitor cooling systems, servers, and critical infrastructure.

Industry benchmarks show that smaller facilities of 1-5 MW require roughly 8 to 15 staff, medium-sized centres of 5-20 MW need around 15 to 35 employees, and large facilities above 20 MW employ about 35 or more people. Even so, employment does not scale proportionately with power use.

For instance, a 40 MW facility may have only around 45 workers, while hyperscale centres above 100 MW often run with even fewer people per megawatt because of automation and standardized systems. This raises a key question: if data centres take up land, water, and electricity but generate limited jobs, are they truly beneficial for India’s workforce?

The US CLOUD Act

The US CLOUD Act gives American authorities the power to demand data from cloud providers, regardless of where that data is physically stored. This means that even if Indian data is hosted in India, US agencies could still legally request access if the cloud company has a presence in the United States.

Importantly, this law does not apply only to US-based firms. Any company that operates in or has legal ties to the US falls under its scope. Courts can also compel parent companies to hand over data held by their foreign subsidiaries.

This raises serious concerns about India’s data sovereignty. If sensitive government, corporate, or citizen data sits inside data centres run by US-linked firms, India may not have full control over who can access that information.

India Could Have an Ireland Moment

Ireland offers a cautionary example of what could happen if data centre growth outpaces energy capacity. In 2023, data centres consumed 21 percent of Ireland’s total electricity, up from just 5 percent in 2015, according to the Central Statistics Office.

Urban households used 18 percent of electricity, and rural households used 10 percent, meaning data centres alone consumed more power than all urban homes combined. Projections suggest that by 2026, data centres could use as much as 32 percent of Ireland’s electricity. This surge has strained the national grid so badly that Ireland has paused new data centre construction in Dublin and surrounding areas until 2028 due to blackout risks.

Similar trends are visible across Europe. In Denmark, electricity use by data centres could increase sixfold by 2030. These examples show that India must carefully plan energy capacity before rolling out massive cloud infrastructure, or it may face grid stress, higher power costs, or supply shortages.

The Storage Box Trap

There is a growing fear that India could fall into the “storage box trap.” This means becoming a mere warehouse for foreign data rather than a creator of digital innovation. Hyperscalers may build gigantic data centres in India, but the real profits, technology, and intellectual property could remain in the US or Europe. India would provide land, cheap power, and tax benefits, while Big Tech keeps control over cloud platforms, AI tools, and software ecosystems.

If India only hosts servers but does not develop its own cloud companies, AI models, or tech platforms, it risks staying a back-end player in the global digital economy. The country would gain infrastructure but not technological leadership.

India Becomes the Toll Booth

By requiring foreign cloud firms to route Indian customers through local resellers, the policy effectively turns India into a “digital toll booth.” While this brings some foreign investment, it locks India into a model where it mainly earns rent rather than building its own global tech champions.

Domestic cloud providers pay a standard corporate tax rate of about 25.7 percent, while foreign hyperscalers get a 0 percent tax holiday until 2047. This creates an uneven playing field that makes it nearly impossible for Indian firms to compete on price.

Industry executives warn that this could shift market power further toward three global giants like Google, Microsoft, and AWS, in a country that already has some of the lowest data-centre rental costs in the world.

This imbalance could also hurt upcoming listings of Indian data-centre companies such as Sify Technologies, Yotta Data Services, and ESDS Software Solutions, as investors may see them as weaker competitors against tax-free global players.

How Is the Industry Reacting?

Nasscom

Industry body Nasscom welcomed the proposed tax holiday, saying it clearly signals that India wants to attract long-term global investment and expand its data-centre and computing capacity. According to the organisation, allowing a 15 percent margin over cost under safe harbour rules gives multinational firms clarity on pricing and reduces the risk of tax disputes.

Nasscom also argued that the policy helps remove past confusion around how cloud services and data-centre operations should be taxed. By distinguishing between the two, India strengthens its position as an investment destination.

The statement said: “On a broad reading, the combined design of these measures helps address long-standing interpretational challenges by clearly separating cloud service activity from data centre operations and aligning India’s taxing rights with arm’s length remuneration, thereby improving ease of doing business and investment confidence.”

Sagar Vishnoi – Future Shift Labs (Director and Co-Founder)

At the same time, not everyone in the ecosystem is fully convinced. Sagar Vishnoi, Director and co-founder of Future Shift Labs, noted that while the government is clearly pushing for AI growth, the policy does little to directly support Indian deep-tech startups.

He pointed out that since foreign firms must serve Indian customers through local resellers, smaller Indian companies may end up fighting for reseller margins instead of getting stronger direct incentives from the government.

Vishnoi also warned that a massive influx of data centres will sharply increase demand for electricity and water, and therefore, fiscal incentives must be accompanied by strict sustainability and green-AI policies.

Bharat Digital Infrastructure Association (BDIA)

The Bharat Digital Infrastructure Association, which represents domestic data-centre operators, has drafted a seven-point policy charter that it plans to submit to the government. Their main demand is to create a more balanced and fair framework for Indian companies.

BDIA secretary general Abhishek Bhatt acknowledged that the tax holiday will attract investment and improve infrastructure, skills, and supply chains. However, he stressed that the current design benefits only foreign firms while offering nothing to Indian cloud and data-centre players.

He said the policy may even push Indian companies to set up offshore structures instead of strengthening operations within India. Bhatt emphasised that any new policy must actively promote indigenous technology, local innovation, and Indian-owned digital infrastructure.

BDIA also highlighted a clear asymmetry: foreign companies get a tax holiday till 2047, while Indian firms running similar data centres must continue paying the regular corporate tax of 25.7 percent.

Piyush Somani – ESDS (Managing Director)

Piyush Somani of ESDS argued that success should not be measured merely by how many megawatts of data-centre capacity foreign companies build in India. He said the real test should be how much of the global cloud economy’s value India controls, in software, platforms, intellectual property, and innovation.

Drawing a comparison with the Indian IT services boom, Somani noted that India succeeded not just because of cheap labour, but because it built globally competitive companies. He concluded that India must aim to be a “cloud superpower and not just a cloud warehouse.”

Sunil Gupta – Yotta (Chief Executive)

Sunil Gupta of Yotta took a more optimistic view of the Budget announcement. He described it as structurally positive and said it will expand the overall market rather than simply shifting business from Indian firms to foreign ones.

From an IPO and investment perspective, he believes the policy improves long-term demand visibility, capacity utilisation, and strategic importance of India-based cloud and AI infrastructure providers. Gupta clarified that the intent of the policy is export-driven, not meant to subsidise domestic cloud usage.

He also pointed out that there is no tax concession on cloud services sold to Indian customers, which means Indian and foreign companies compete on equal terms within the domestic market.

At the end of the day, the 2047 tax break is a mixed decision for India. It will certainly bring more investment, better digital infrastructure, and some jobs, which is good for growth. But at the same time, it could make India too dependent on foreign tech giants, strain electricity and water resources, and put local companies at a disadvantage.

The real success of this policy will depend on how India uses this opportunity, whether it simply hosts servers for global firms or also builds its own strong cloud and AI industry. If the government supports domestic players, protects data, and plans energy carefully, this policy can help India grow. If not, it could end up helping Big Tech more than India itself.

Disclaimer: The views and investment tips expressed by investment experts/broking houses/rating agencies on tradebrains.in are their own, and not that of the website or its management. Investing in equities poses a risk of financial losses. Investors must therefore exercise due caution while investing or trading in stocks. Trade Brains Technologies Private Limited or the author are not liable for any losses caused as a result of the decision based on this article. Please consult your investment advisor before investing.

The post 21 Year Tax Holiday for Foreign Cloud: A Red Carpet for Big Tech, a Red Signal for Local Heroes? appeared first on Trade Brains.

What's Your Reaction?